This article was published in April 2025 and has not been edited to acknowledge the end of The Future is Brighter campaign.

Most of us in Stamford support the same vision for the future. We want safe community spaces to build connection, family friendly infrastructure that works for everyone, and housing our residents can genuinely afford. But despite agreeing on what we want, we can’t seem to make it happen.

Instead, we get division and petty fights across administrations. Why is it so hard to get what we all clearly want?

The answer is we have a culture of fear, and a system that rewards that fear. That system is the Board of Representatives. I’m going to explain why Board of Representatives doesn’t work and why Stamford is better off without it.

To understand this, we need to separate why the Board of Representatives doesn’t work from the politics of issues they try to address. Politics is complex. It is a combination of policy expertise and balancing the interest of various groups. Stamford’s Board of Representatives doesn’t fail because politics is complex, it fails because of its culture of fear. To separate these two things, I’m going to start with an analogy. It’s an oversimplified, but it’s a useful place to start.

Analogy

There’s three neighbors at a barbecue in Stamford and they’re deciding where to eat. Let’s give them typical names that are easy to remember like Aloysius, Berengar, and Niles. Aloysius wants to order food from El Jefe’s on East Main Street because it’s the best taco truck in the city. While Berengar wants Elm Street Diner, because he lives in Norwalk and only knows Stamford through Instagram. Niles, however, rejects both options.

The neighbors ask Niles what he would prefer and the mood shifts. He looks around nervously, demands your phones, and seals them in a box you’ll Google later and learn it’s called a Faraday Box. He looks at you and explains.

“All this is necessary, because we’re being watched — by the government!” he says. “A race of lizard people have infiltrated the government and contaminating the food supply to transform people into reptiles.”

Niles says when it comes to ordering food in Stamford… “nothing can be trusted.”

At this point, the neighbors remember Niles — at some point in his life — got big into conspiracy theories. Usually, he’s a normal guy, but sometimes a topic comes up and his brain spirals into a destructive worldview of negativity and distrust. It is this worldview that prevents the group form making a decision.

This is an extreme analogy, but it describes a similar phenomenon that happens in Stamford’s local government.

In Stamford’s Democracy, we elect representatives — like the mayor — to make decisions on our behalf. We elect representatives, because ordinary people don’t have time to research every decision and weigh the pros and cons of which decision is best. If we believe our representative is out-of-step with the public, the public has means to express that through public meetings, organized protests, or lobbying other officials to check the mayor’s power. These are the fundamentals of democracy and they assume participants engage with the government in good faith. That was a safe assumption to make when the Board of Representatives was first created back in 1949.

Back in the 1940s, the only way you could spread an idea was through a public meeting. This meant spreading ideas had a social element. If someone lacked social standing or respect, their ideas didn’t gain traction — which naturally prevented conspiracy theories from derailing public discussions. If you went to a meeting and constantly accused your neighbors of contributing to a lizard-people conspiracy, you probably wouldn’t have the trust or respect to influence the community’s decisions.

Today, things are different.

Technology — such as the internet and social media — has opened up communication to more people. That has brought a lot of benefits. It’s made historically marginalized people more involved in our society, which in turn has made our democracy more fair and representative. That’s clearly a good thing, but there’s an uncomfortable truth we rarely discuss. There is clearly a limit to how far we want democracy to go. For example, we don’t want people outside of our community to make decisions for our community. We also don’t want meetings hijacked by disruptions that make decision-making impossible. We can debate where the limit of democracy should be, but we should acknowledge it exists. Our government is not innately better when more people are involved. There is a limit. We know this, because we set similar boundaries in our own personal lives.

Let’s go back to the analogy.

The two neighbors hear Niles’ conspiracy and immediately conclude what needs to happen. They tell Niles he’s not thinking clearly, and he’s getting in the way of making a decision. The neighbors understand Niles’ paranoia isn’t something he chooses to believe — it’s from a destructive worldview — so they have compassion for him, but having compassion doesn’t prevent them from seeing things clearly. And clearly, Niles shouldn’t be blocking the group from making a decision. Not because they dislike Niles, but because his worldview is incompatible with group decision making.

In your own personal life, it is very likely a neighbor like Niles will listen to your feedback and value your relationship enough to adapt his behavior.

In local politics, what is more likely is someone like Niles will respond to criticism by insisting their worldview even more aggressively. In fact, Niles will likely include you as a personal enemy of his worldview.

Every ordinary person understands this response is unacceptable. If someone responded in this way in our personal lives, we would recognize their behavior is ripping apart the cohesion of the group through accusations and paranoid thinking. We wouldn’t invite that person to future outings and they would become isolated from the neighborhood.

Yet for some reason, people believe this type of behavior is acceptable in local government.

Stamford’s Board of Representatives does not debate lizard people conspiracy, but they do push a similarly distorted worldview I call “anti-social nihilism.” This worldview is built on two damage beliefs. Those beliefs are “other people are bad” and “nothing can be trusted.” The Board of Representatives spends a lot of time justifying this view — in the same way Niles would love to justify his view for his lizard people conspiracy — but their justification is not the point. The point is this worldview makes group decision-making impossible and blocks Stamford from getting anything done.

I am running for mayor because I believe this is the problem that needs to be resolved before anything else can be addressed in Stamford. Every policy decision in Stamford’s local government needs to pass through the Board of Representatives. The system was designed to be a “check” on the mayor’s governance of Stamford, but in practice the board has become an entity against virtually everything. Again, not because of policy differences or the complexity of politics, but because of a culture of fear identical to a lizard people conspiracy theory.

The end of this article will explain how to fix this. First, I want to demonstrate how this worldview has harmed Stamford by looking at two different examples from Stamford’s recent history. In both examples, the issue is not the complexity of the issue. It is the negativity of anti-social nihilism and how it prevent group decision-making.

How anti-social nihilism harms Stamford

Example #1: Fracking Ordinance, 2019

The first example comes from the previous administration. So if you think the issue of anti-social nihilism only started in the past 4 years, you are mistaken.

In 2019, the Board of Representatives created a self-inflicted operational nightmare that cost the city hundreds of thousands of dollars because of their own bad ordinance.

The ordinance was to ban fracking waste in Stamford and it was pitched as an environmental issue by the representative who proposed it. The ordinance was written so any business working with the city had to sign an agreement certifying nothing in their business included fracking waste. The problem with this fracking ban ordinance is it used broad legal language. The ordinance asked businesses to “certify under penalty of perjury” they didn’t use fracking waste.

The phrase “under penalty of perjury” might mean anything to the average person — or apparently to the board — but for a business with a legal department it is incredibly serious. In practice, this legal language meant businesses had to guarantee their entire supply chain was completely free of fracking waste. If they certified this and later discovered they were wrong, they would face the legal consequences of perjury — including potential imprisonment.

The city’s own law department and engineering department warned the board this requirement was overly broad and could cause issues.

“For them to certify that, as the language says here, ‘we hereby certify under penalty of perjury that […].’ I have a hard time believing they’re going to sign that.”

City Engineer Lou Casolo

Now you might think: “Good! Businesses shouldn’t be using fracking waste.” But even in your daily life, you couldn’t realistically certify this. It’s nearly impossible to know exactly what’s in every product or material you use. Almost every container, appliance, or household item contains plastic — a material derived from oil or natural gas. If you can’t certify this in your own life, how could a business do it for an entire supply chain?

This exact point was made to the board:

“Some things that might contain a natural gas product: paint, roofing materials, tires, caulking materials, any type of liquid with petroleum in it. De-icing, heating oil… There’s a lot of things that could be manufactured with a recycled product. I’m not saying they come from fracking waste, but the language here is broad.”

City Engineer Lou Casolo

City staff didn’t oppose the ordinance. They just suggested changing the wording so it wasn’t so broad. The Board didn’t trust the law department’s advice, because in the board’s worldview: nothing can be trusted. They ignored professional advice and you can guess what happened next.

The following year — in the middle of Stamford’s road paving season — the city’s largest asphalt supplier O&G refused to sign the contract. When asked why, they pointed directly to the “by penalty of perjury” clause.

And here’s the real kicker: While the mayor tried to get the ordinance fixed, the city ended up buying asphalt from a smaller local business called Grasso. But Grasso doesn’t produce asphalt. They buy it from O&G. That means the ordinance accomplished nothing. We got the same asphalt, from the same place, with more paperwork and legal risk to a local business.

A few months later, the board finally fixed the ordinance. When asked about the mistake, the representative who proposed the ordinance claimed the whole situation was a political stunt designed to embarrass the board.

Now, I actually commend this board member for pursuing an ambitious ordinance on an issue people in Stamford care about. But this vague and conspiratorial thinking illustrates exactly what I mean by anti-social nihilism. The Board has no appreciation for subject matter experts. Instead they perceive any opposition to a nefarious conspiracy — almost as if a group of lizard people are out to get you!

The problem with believing in anti-social nihilism is… if you look at other people with suspicion — because you think other people are bad — and if you can’t trust professional advice — because nothing can be trusted… you’re not going to get anything done.

This is why the board hasn’t been able to accomplish much of anything for years, and things have not improved since 2019. It’s six years later and the same board members who passed this ordinance still insist the law department is out to get them. That wasn’t the case then and it isn’t the case now.

Anti-social nihilism isn’t a worldview you can “debate.” In the same way you can’t debate the merits of a conspiracy of lizard people. It is a destructive worldview and even reality itself can’t persuade people out of it — which we can see in the next example.

Example #2: West Main Street Bridge, 2025

This one’s more recent — just last month. In March 2025, the Board of Representatives revived a discussion about the West Main Street Bridge.

If you’re new to Stamford politics, the West Main Street Bridge is essentially the most embarrassing governance failure in our city.

The bridge was closed back in 2002. Originally built in 1888, the bridge predates cars. It uses a design called a lenticular truss, which was popular in the Victorian era when the main transportation was by horse or foot. These bridges simply can’t handle the weight of modern vehicles without constant and costly repairs. There are fewer than 50 lenticular truss bridges left in the United States and one of them happens to be in Stamford.

After almost 100 years of car traffic and constant repairs, the West Main Street Bridge deteriorated enough to justify its closure. The problem is this bridge served as a gateway connecting residents from the West Side directly to downtown without forcing them onto a busy arterial road like Tresser Boulevard. For the past 25 years, the city has debated what to do next, but realistically there are only two options. The city can either:

- Repair the bridge but restrict it to pedestrian and bicycle use to avoid continuous damage from vehicles.

- Or replace it entirely with a modern design built for cars.

Unsurprisingly, the Board of Representatives has only favored a third and completely impractical option: repair the existing bridge and reopen it to car traffic.

Even if the board got what they wanted, reality remains the same. The bridge’s design can’t handle cars, because when it was designed there were no cars. No amount of wishful thinking can change the reality this bridge doesn’t provide what we need from our infrastructure.

Other communities across the country have had these bridges, recognized reality, and replaced them a long time ago. Our Board has been told by our own city engineers and a slew of consultants this bridge can’t support cars, but they keep ignoring reality. Why? Because other people are bad and nothing can be trusted.

The board chooses to not trust reality like physics. If you so regularly discard reality, you are not capable of finding a solution to any problem. This is anti-social nihilism. It is a worldview that builds nothing and helps none. Which is exactly what we’ve got from this board. Nothing. Sometimes, even less!

At one point, the city was awarded an $850,000 grant to repair or replace the bridge. The board has delayed action for so long the grant expired in 2022.

Our local government is so dysfunctional it can’t spend free money.

If you listen to the public meetings about the West Main Street Bridge, you can identify the reason why people are so attached to this worldview. When you believe other people are bad and nothing can be trusted, you’re not looking for a solution to the city’s problems. You’re looking for a comfort for your own misery. Somehow you’ve become very negative. You believe everything is bad, it’s only getting worse, and no one knows how to fix it. This is a comfort you tell yourself and it is not true.

This is a culture of fear. It is wasting our time and money.

More importantly, it’s making us miserable.

What’s the solution?

I could do an article every day about the failures of the Board of Representatives and how it is driven by anti-social nihilism, but I don’t want to do that. I believe the board members are as much victims of this negativity as they are perpetuators of it. I think identifying the problem and putting forth a solution gives an opportunity for people to correct the mistakes they’ve made. This campaign is about building a brighter future for Stamford. Many of these representatives could contribute to that future if they leave this worldview behind.

The first step for accomplishing a brighter future for Stamford is to break down the system that creates our culture of fear. That means breaking down the Board of Representatives — which means electing a new board. This campaign is assembling a coalition of 40 future-forward citizens to do exactly that.

I am recruiting 40 candidates for all 40 seats on the Board of Representatives. The platform for each candidate is simple: “Vote for me and I will eliminate my own position.”

My personal view is we should break down the board in its entirety. You can read Solution #7 for more details on what that means. I recognize this may be an extreme proposal, so I have broken down seven different proposals below. All of these solutions would address our culture of fear and bring about a brighter future for Stamford — it’s just a matter of how far we want to go.

If you are interested in becoming a candidate for the Board of Representatives, contact me directly. Don’t worry about your qualifications, I can help with that. All you need is the courage to try.

This year, we’re going to give Stamford voters control over our city’s destiny.

Solution #1: Reduce the size of the board

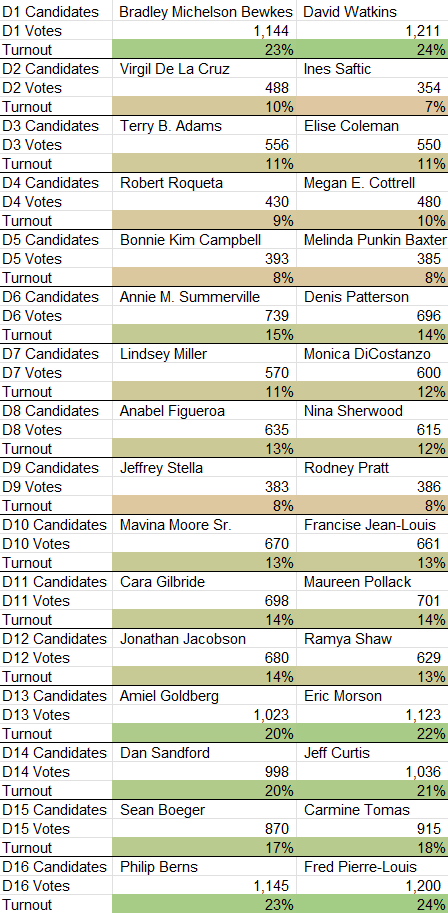

The Board of Representatives currently has 40 members — two representatives for each of the city’s 20 districts. This is way too many representatives and we know that because voter turnout for these elections is extremely low. Some people get elected with less than 10 percent turnout. We’re talking about elections where someone with a district of 5,000 voters wins with a total of 400 votes. That’s an 8 percent turnout.

In fact, a recent poll showed most residents can’t name their representative (55.5%), and even fewer knew their representative was up for re-election this year (67.9%). In the last election — 2021 — a dozen candidates ran unopposed.

Nobody wants to do this job and honestly, why would they? The meetings are long, boring, and unproductive.

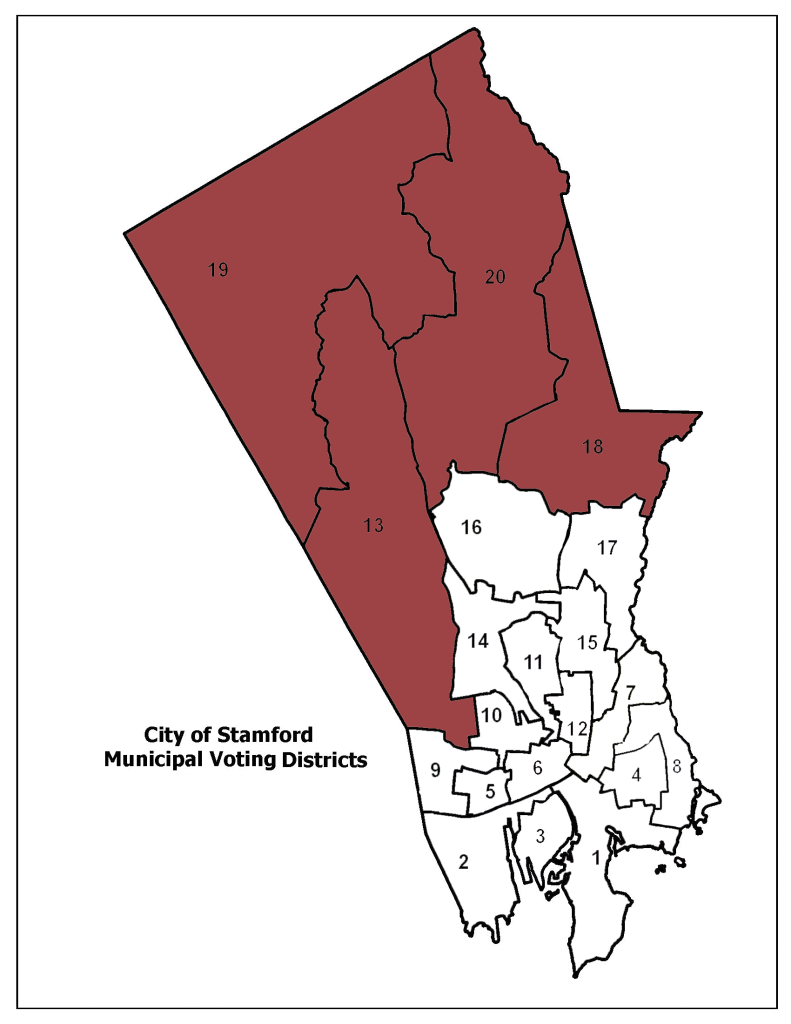

Many of these districts don’t even have distinct needs or interests. Glenbrook and Springdale. Downtown and the South End. The Cove and… the Cove again. These districts have the same concerns, infrastructure, and point of view on the city. Do we really need 8 different representatives for North Stamford? I don’t think so.

We could reduce the Board of Representatives from 40 members to 10 members by changing one line of text in the charter.

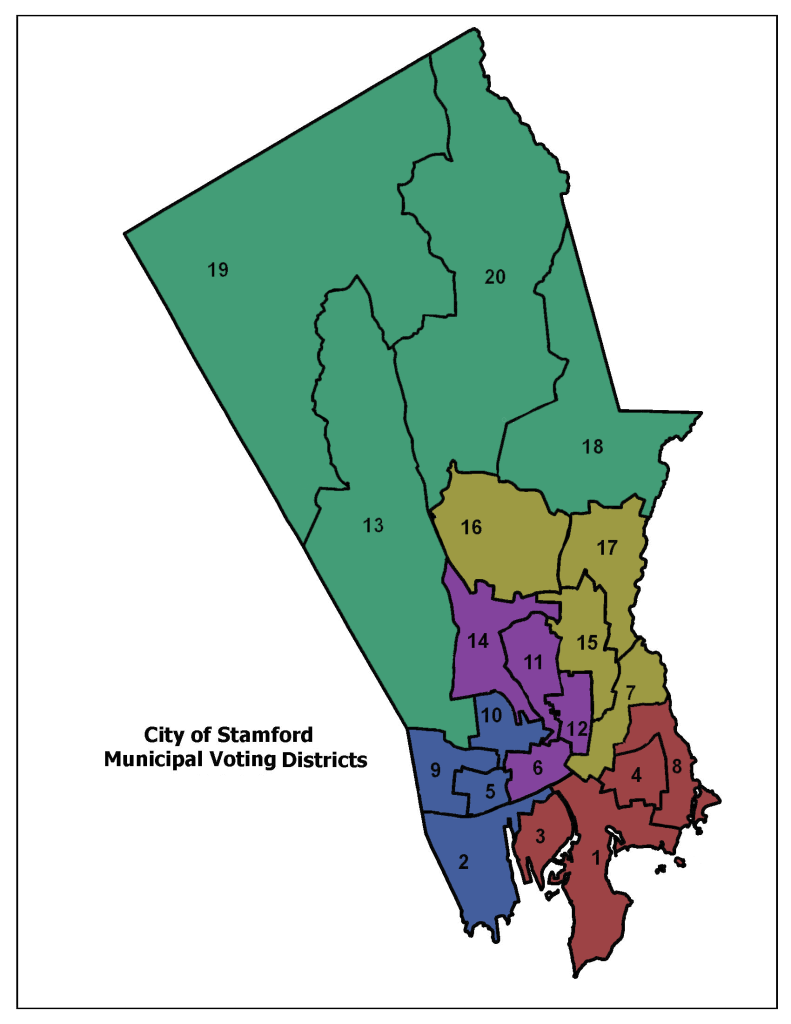

Instead of “Two members of the Board of Representatives shall be elected by the qualified electors of each of the (20) voting districts of the city,” (Sec. C1-80-4 Election of Board of Representatives). Change it to “(5) voting districts.”

We wouldn’t even need to redraw the map — just combine what we already have. Each of the 5 new districts would be made up of 4 of the old districts.

Fewer representatives would encourage competition between candidates and higher voter participation.

Solution #2: Staggered elections

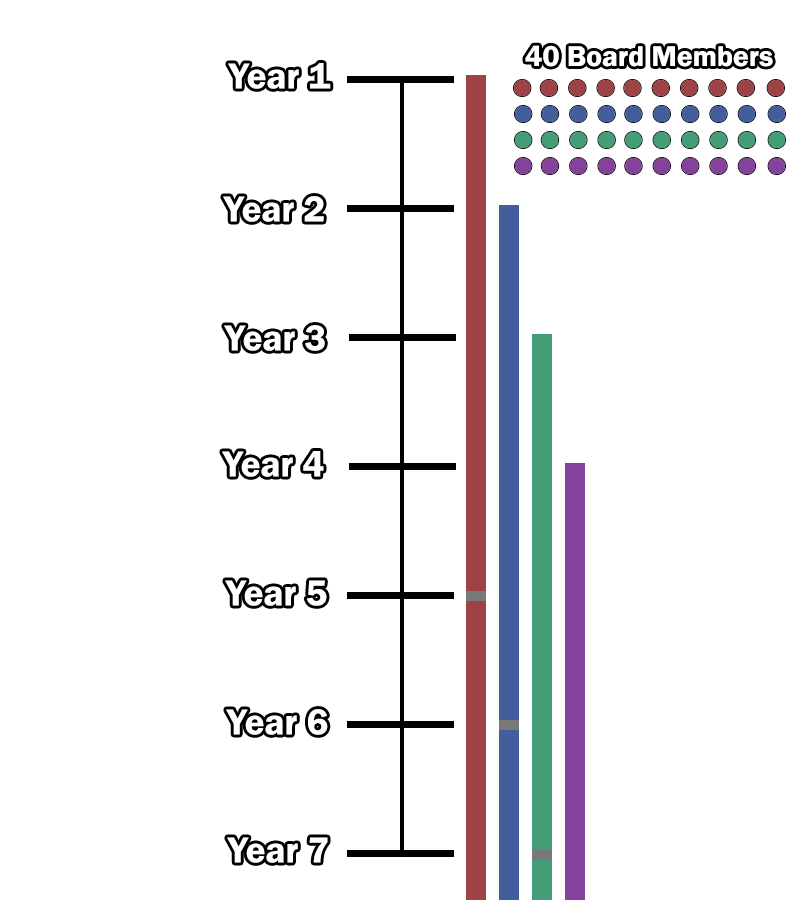

If Stamford prefers keeping all 40 representatives, another good option is staggered elections. Here’s how it would work.

Elections are already staggered for Stamford’s Board of Finance and Board of Education. Staggered elections mean voters have a say every year. Right now we have all our political frustrations vented once every 4 years. Staggered Elections would enable a more fluid democracy and provide greater accountability. If the board claims they are the “true voice of the people,” we would see if that was true every year.

Solution #3: Reduce Board of Rep terms to 2 years

Another alternative is simply reducing representatives’ terms from four years to two year. In fact, Stamford had two-year terms until the 1995, when Mayor Malloy campaigned to extend his mayoral term and included extending the term of all board members.

Shorter terms make sense for board members, because of how frequently board members resign mid-term. Since 2021, a fourth of the board has resigned and replaced with an appointed representative. This is a good indication these terms are too long. It also means more accountability for the whole board.

Solution #4: Pay the board members

A major problem for Stamford is getting anyone to run for office. Right now, serving on the board is a volunteer position — which means members are typically wealthy, retired, or unemployed. This doesn’t represent our community.

Paying our representatives a modest, part-time salary — say $30,000 a year — would attract higher quality candidates. Of course, paying all 40 members would be pretty expensive at $1.2M a year. But if we combined reducing the board to 10 members, then the total cost would be $300,000 — roughly the equivalent of two city department heads’ salaries. I’d much rather pay for 10 effective representatives than 40 ineffective volunteers.

Solution #5: Citywide representatives

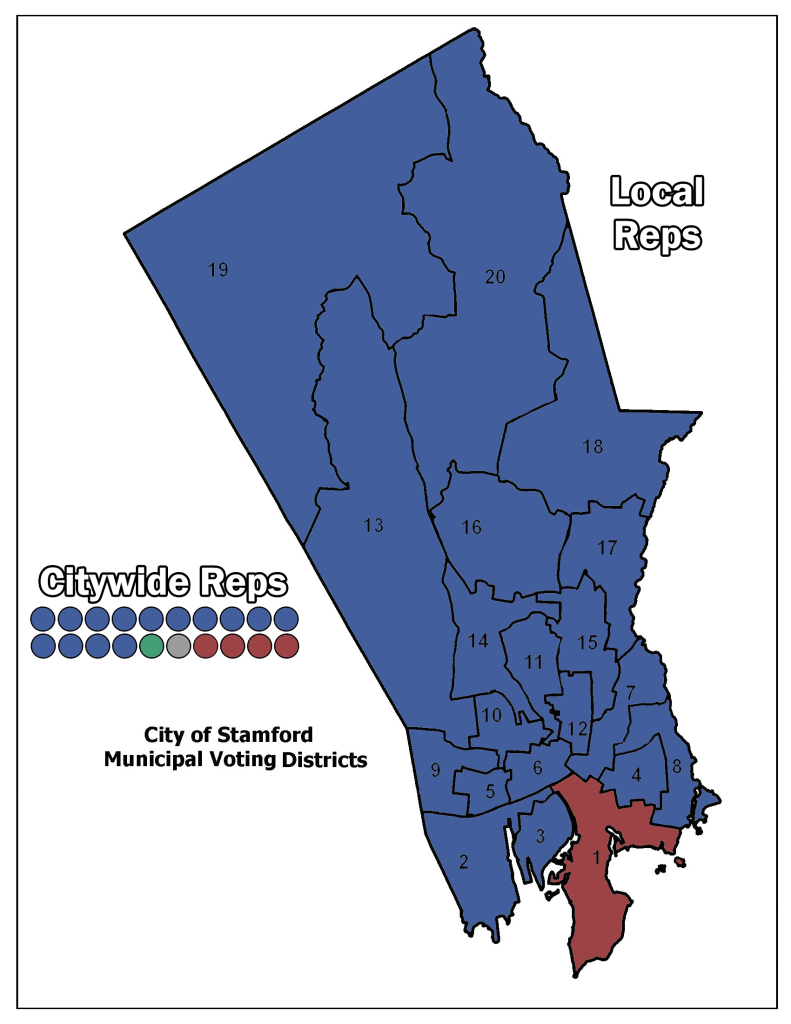

Right now, Stamford elects two representatives from each of its 20 districts.

We could change this system so we elect one representative from each district, and elect the other half citywide. This creates two types of representatives: local reps focused on neighborhood concerns, and citywide reps looking at broader issues for all of Stamford.

This proposal is particularly important for anyone who’s not a Democrat. Stamford is dominated by Democrats. The current 40-member board has 37 Democrats. Adding citywide representatives would trigger Connecticut’s minority-representation laws, ensuring at least one-third of board members come from other parties or unaffiliated candidates.

If you’re a Democrat, that might sound like something you don’t want, but minority representation encourages honesty. Right now, we have another candidate for mayor who was a Republican for 8 years, then switched parties 5 months ago to run for office. This type of dishonest political opportunism is encouraged when a city is dominated by one party. We want people to be honest about their values and where they disagree on policy decisions.

Citywide representation would encourage long-term planning, compromise between board members, and a more balanced government.

Solution #6: Data on public sentiment

This solution might be a little too futuristic for some voters, but I promise you it fixes the problem we’re talking about.

Government today is behind the times. Businesses constantly measure consumer satisfaction with data, but local governments rarely gather meaningful public feedback outside of public meetings and elections.

We could fix this by requiring an annual citywide poll of Stamford residents. We could limit this poll to 10 questions to keep it simple and two questions would always need to appear.

Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the Board of Representatives?

Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the Mayor?

Since every taxpayer has an ID, this survey can be secure and trustworthy. Stamford’s Chief Technology Officer could easily implement this, providing elected officials clear guidance from residents every single year — not just during election season.

Solution #7: Break down the board of reps

Historically, Stamford’s board was never supposed to have 40 members. The board was originally proposed as a 10-member board, but that proposal lost by a couple hundred votes because it didn’t cater to special interests at the outer edges of the city.

Today, the Board of Representatives is not only large, it’s redundant. The Board of Finance carries out the main function of the Board of Representatives which is approving the budget and specific contracts. The Board of Reps have the added powers of passing ordinances and approving mayoral appointments, but these functions could be moved to the Board of Finance. This might warrant renaming the Board of Finance the Board of Approvals, Finance, and Appointments (or BAFA).

As for the ordinances, let’s be honest: these ordinances have no impact. Stamford passed a plastic bag ban six years ago and every business I go to gives me a plastic bag. Ordinances without enforcement are just symbolic gestures. Like we’ve got 40 representatives playing house.

Besides, the board wasn’t meant to be a legislative branch. It was meant to be a check on the mayor. We don’t need 40 mini mayors talking about how they would change city policy if they were mayor. They can’t change policy. Apparently some of them don’t even know this.

Here’s this clip I found while doing research for this video. It comes at the very end of a 3-hour committee meeting about housing:

We don’t need these people attempting to backseat manage the city. We need a smaller group of effective decision makers who can actually move Stamford forward.

Look, here’s the most important thing to understand about representative democracy. Being a representative is difficult. And being a good representative is rare. Therefore, having a lot of representatives increases the chance your good representatives get squeezed out by bad ones. America was founded on representative democracy rather than direct democracy, because most people don’t have time to get educated about every decision made by the city and weigh the pros and cons. The most effective democratic model consolidates decision-making to fewer and more capable hands. It isn’t anti-democratic to point this out, this is how representative democracy was always intended to function.

We don’t need 40 volunteer board members serving four-year terms. What we might need is 10 well-paid representatives serving two-year terms.

More likely, we don’t need the board at all.

How does this all happen?:

If you’re uncertain about any of these proposals, the good news is you don’t need to figure it out right now. The process for any of these changes requires the following:

- Step 1. We need to elect at least 27 new members to the Board of Representatives. That’s what this campaign is focused on doing. If you want to help. Email me at arthur@thefutureisbrighter.com.

- Step 2. A 2/3 majority of the Board of Representatives needs to vote in favor of something called a Charter Revision Committee. We had one of these in 2023, but it didn’t succeed because the proposals were a waste of everyone’s time.

- Step 3. After this vote is approved, the board will interview members of the public to form the charter revision committee. Of which, I can assure you there will be many people interested.

- Step 4. This committee will work independently from the board for a few months to put together their proposals.

- Step 5. The committee will present their proposals to the board, which approves/rejects each specific proposal. They will then draft language that will be proposed to the public to vote on.

- Step 6. The board can choose to bundle the proposals into one big item, or it could present each of these 7 recommendations as their own item to be voted on separately.

- Step 7. An election would be scheduled – ideally in 2026 but may get delayed to 2028 — and the public would vote what they think is best.

- Step 8. The results would be tallied and these changes would take effect a month after the election.

It’s a long process and it’s a risky process, but it’s not impossible. We can do it. We have all the motivation for why and all the plans for how. Now comes your part.

If you are even a little bit interested in running for the Board of Representatives, contact me directly. It doesn’t matter if you’re a Republican, Democrat, or unaffiliated. I can help you. I don’t care about your party, and I don’t care if you think you’re not qualified.

Do you believe Stamford’s future is brighter? Are you committed to these proposed recommendations to break down the system of fear that’s holding us back? If your answer is “yes,” you are qualified.

My goal is to get 40 people to run for all 40 seats, but if that doesn’t happen. There is option B.

Option B

If we don’t get enough candidates for all 40 board elections, then I will submit myself as a write-in candidate for every single election. If voters don’t like their options — and the options are likely to run unopposed — then this gives them an option to vote against the status quo.

Obviously, it is impossible for me to “win” every election but that’s not the point. The point is to show Stamford citizens they can run for office. If I can win in your district: so can you. Ideally, you run this election but if you’re not ready for that then Option B will give you the motivation for next election cycle.

That’s what my campaign is about. We’re going to give Stamford residents reasons to believe the future can be brighter. We’re going to inspire people to take action consistent with that belief.